In the 11 March 1854 edition of the Los Angeles Star it was reported that a detachment of the paramilitary organization had captured some horse thieves at the Rancho La Puente, owned by John Rowland and William Workman in the eastern San Gabriel Valley.

The next week a notable occurrence took place, when on Monday the 13th, the first legal execution conducted in Los Angeles was carried off--this nearly four years after the American legal system was implemented in the county.

Ygnacio Herrera was convicted in the District Court of the murder of Nestor Nartiago [probably Artiaga?] on 17 December 1853 and then sentenced to be hung. The Star's article was remarkable terse and began with the strange statement that, on the 13th, Herrera "celebrated the first judicial execution in this County." This might have been a snide comment about the fact that it took so long to secure a capital murder conviction, despite all of the homicides that had taken place. While the paper noted that the convict "was a Mexican and a soldier," it made no reference to the crime or trial in the piece.

The paper did report that "the arrangements of the Sheriff [James R. Barton] were carried out with much solemnity and propriety, and the execution was witnessed by thousands of people." In those days, executions were very public and people could gather on the hills surrounding the jailyard to view the spectacle.

It was also noted that "the prisoner made an address in which he asserted that there was no justice in our courts" and that "there was considerable sympathy for him manifested among the native population," suggesting that there was a racial or ethnic element to his remarks, even though the victim was a fellow Latino.

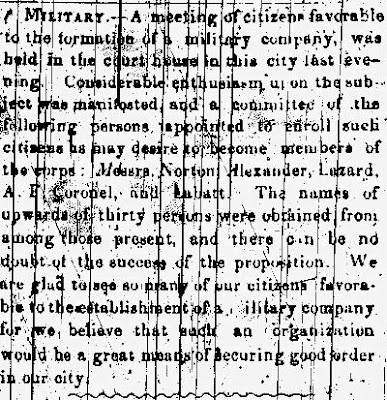

|

| The 4 March 1854 edition of the Los Angeles Star reported on the first legal execution in the city and the presence of the Los Angeles Rangers paramilitary group. |

Finally, the Star observed that "a detachment of the Rangers, both horse and foot was in attendance," though it was not stated whether the organization's presence was for general observance, security, or for some other reason. It is tempting to believe that, because of the "considerable sympathy" manifested by Herrera's fellow Latinos, that the Rangers were there in case of any attempt to break the condemned man free, but this is pure supposition.

A couple of weeks later, in the 4 March edition of the Star, it was reported that an El Monte meeting held on 23 February culminated in the creation of "a force auxiliary to the Rangers." Twenty-six men signed up as active members, led by Captain John H. Huhes, First Lieutenant James H. Weatherbee, and Second Lieutenant Alexander Puett.

The paper went on to state that " it is in the intention of the company to make immediate application to be received as a military police force and to be supplied with arms, etc." With the organization of the El Monte contingent, it was observed that there were then two mounted units and one foot branch of the Rangers, comprising seventy-two men.

For the Star, the fact that the Rangers had been active in pursuing criminals was evidence that "so long as there are thieves and villains, their organization will be a necessity to the community." The article concluded by noting that a meeting would soon be held among the various branches t choose battalion officers and "for a more perfect organization of this force."

If there was such a gathering, it was not reported on in the Star, though the paper did note the first anniversary of the formation of the Rangers in its issue of 10 August.

As matter-of-fact as the press reporting about the Star was concerning the formation and the activities of the Rangers, the next post moves to a more fanciful and expressive recollection of the organization from one of its founder members, Horace Bell, through his 1881 memoir Reminiscences of a Ranger.