For those interested in the history of nineteenth-century Los Angeles, there are two autobiographies that are standard reading: that of merchant Harris Newmark, who arrived in the town in 1853, and the one written by Horace Bell, who predated Newmark by a matter of months, coming to town in 1852. The difference between the two is dramatic, however,

Newmark's book, Sixty Years in Southern California, published in 1913, is a collection of factual reminiscences laid out chronologically, offering relatively little commentary, and, frankly, lacking a sense of narrative and story. Subsequently, many people use Newmark almost like a reference book, picking out the book when they want to learn more about a person or event. He has been and will continue to be utilized here on this blog with great frequency.

Bell is an entirely different chronicler in his two works, Reminiscences of a Ranger (1881, reprinted in 1927) and On the Old West Coast, published in 1929 after his death. While he liked to refer to himself as a "truthful historian," Bell was far more interested in telling rollicking, action-packed, character-based tales than laying out a series of facts. Anyone with a good general understanding of the 1850s, which is the period in which Reminiscences largely takes place will be able to find many substantial errors and energetic exaggerations in Bell's text.

This is, in no way, a suggestion that Bell not be consulted. His books are highly entertaining, but they need to be taken with a factual grain (or two or dozens) of salt.

A native of Indiana who came, as so many thousands did, to Gold Rush California in 1850 when he was barely out of his teens, Bell migrated south to Los Angeles in late 1852 where he had an uncle, Alexander Bell, a prominent merchant (though, strangely, Bell never refers to him as a relative in Reminscences when he talks about him at all.)

His detailing of the stage ride from the rudimentary harbor at San Pedro to the village of Los Angeles is the template for how the rest of Reminiscences is written. The prose is lively, full of alleged, colorful quotes by the people Bell wrote about and replete with italics and exclamation points to hammer home the feeling about the wild frontier community that the author was determined to make as clear as possible.

While Bell delighted in talking about desperadoes, card sharks, immoral and unethical bigwigs, fallen women, gambling houses and other places of entertainment, and the like, he professed to have an aversion to discussing the horrors of extreme violence and the accompanying atmosphere surrounding much of Los Angeles' sordid criminal history, even as he often betrays himself by doing just that. Still, he claimed that his purpose was to take more of a lighthearted approach, using comedy filled with irony and no small amount of critical commentary about events and persons.

Later an attorney and publisher of a relatively unknown weekly paper, accurately styled The Porcupine, Bell had an acidic, aggressive and confrontational style when it came to those contemporaries he did not like, while he could, on the other hand, be effusive, warm and highly complimentary of those he did. Often the objects of his disdain went nameless in the text, except for some mocking sobriquet, such as "a most useful man" or "Old Horse Face."

When it came to criminal matters, Bell found himself arriving in Los Angeles just as a major event was taking place. Joshua Bean, general of an Indian-fighting militia and owner of a San Gabriel salloon, was recently murdered and, the day after settling in, Bell found "a very small adobe house, with two rooms, in which sat in solemn conclave, a sub-committee of the great constituted criminal court of the city." In other words, he stumbled upon a popular tribunal of citizens acting, ostensibly, in support of the legally-constituted courts in trying the matter of the men accused of killing Bean.

Bell, soon to join a militia of citizens formed to fight crime known as the Los Angeles Rangers (covered here in recent posts) and later a filibusterer with William Walker in Nicaragua, portrayed himself in Reminiscences as diametrically opposed to vigilantism. In mocking tones, he reported upon the "very refined proces of questioning and cross-questioning" utilized in the tribunal and the way in which any contradictory statements made by a defendant who was "frightened so badly that he would hardly know one moment what he had said the moment previous" were considered "conclusive evidence of guilt."

It is interesting in this case to compare Bell's account with that of the sole newspaper in town, the weekly Star, and, in fact, the Bean murder will be covered here in more detail later. For now, it is enough to say that the several men subject to the popular tribunal were, not surprisingly, found guilt and lynched. While it was rumored that the legendary Joaquin Murrieta (or one of the several possible variations of him said to be roaming California) was directly involved in the Bean murder, Bell accepted his presence as an incontrovertible fact.

Having heard the substance of the trial, Bell departed and saved the hanging of the condemned men for a later, dramatic discussion, complete with a rainstorm, bursts of thunder and the like, and went on to talk about how Los Angeles "was certainly a nice looking place" in the midst of a Gold Rush windfall that enriched a great many ranchers and merchants in the small town through the lucrative cattle trade.

His tour on that second day in town, of course, included the more colorful establishments in town, including the many grog shops, gambling dens and other places of entertainment in and around the Calle de los Negros, known by Anglos as Nigger Alley, though the place was actually named for a dark-skinned Mexican who lived there in previous years.

This is where Bell made his famed, unsubstantiated, but generally accepted allegation that "the year '53 showed an average mortality from fights and assassinations of over one per day in Los Angeles." He went on to say that "police statistics showed a greater number of murders in California than in all the United States besides, and a greater number in Los Angeles than in all of the rest of California" for the same year, though there is no citation, naturally, for the sources.

As noted here previously, there are other sources that suggest that the murder rate in Los Angeles was far lower and, almost certainly, far more accurate, but even at a few dozen documented murders in a given year, for a town of just several thousand, the rate is still astronomical. What Bell doesn't discuss in any detail is just why the conditions were present for such a marked rate of murder in Gold Rush-era Los Angeles.

In any case, there is no question that crime and violence were mind-numbingly high in a community lacking monetary and material support for policing and court operations, abundant in young men from many ethnic and racial backgrounds and willing to fight out their differences in many kinds of circumstances, including those fueled by alcohol as well as prejudice, and awash in a sentiment that encouraged personal (or even group) justice over existing legal structures.

Bell's exaggerations serve the purpose of the dramatic storytelling that animated him, even if the grains of truth in his assertions need to be picked out and analyzed at a level of detail and corroboration he studiously avoided. Still, his accounts are valuable because they are so rare and, again, because his style is so fun to read.

The next post takes us to his association with the Rangers and other tales of crime and violence in 1850s Los Angeles.

My name is Paul Spitzzeri and this blog covers the personalities, events, institutions and issues relating to crime and justice in the first twenty-five years of the American era in frontier Los Angeles. Thanks for visiting!

Monday, December 28, 2015

Sunday, December 20, 2015

The Further Adventures of the Los Angeles Rangers, 1854

As 1854 dawned, the Los Angeles Rangers continued to be active in the region as an avowed complement to the county's legal system.

In the 11 March 1854 edition of the Los Angeles Star it was reported that a detachment of the paramilitary organization had captured some horse thieves at the Rancho La Puente, owned by John Rowland and William Workman in the eastern San Gabriel Valley.

The next week a notable occurrence took place, when on Monday the 13th, the first legal execution conducted in Los Angeles was carried off--this nearly four years after the American legal system was implemented in the county.

Ygnacio Herrera was convicted in the District Court of the murder of Nestor Nartiago [probably Artiaga?] on 17 December 1853 and then sentenced to be hung. The Star's article was remarkable terse and began with the strange statement that, on the 13th, Herrera "celebrated the first judicial execution in this County." This might have been a snide comment about the fact that it took so long to secure a capital murder conviction, despite all of the homicides that had taken place. While the paper noted that the convict "was a Mexican and a soldier," it made no reference to the crime or trial in the piece.

The paper did report that "the arrangements of the Sheriff [James R. Barton] were carried out with much solemnity and propriety, and the execution was witnessed by thousands of people." In those days, executions were very public and people could gather on the hills surrounding the jailyard to view the spectacle.

It was also noted that "the prisoner made an address in which he asserted that there was no justice in our courts" and that "there was considerable sympathy for him manifested among the native population," suggesting that there was a racial or ethnic element to his remarks, even though the victim was a fellow Latino.

The case file, which survives, is a very full one, making it a true rarity among the surviving criminal court material from the era and there was plenty of testimony pointing to the guilt of Herrera in the killing of Nartiago (Artiaga), which took place, predictably, in a saloon and which involved alcohol. Herrera, as a former soldier, must have had his sword from his service with him because he ran the deceased through with his weapon.

Finally, the Star observed that "a detachment of the Rangers, both horse and foot was in attendance," though it was not stated whether the organization's presence was for general observance, security, or for some other reason. It is tempting to believe that, because of the "considerable sympathy" manifested by Herrera's fellow Latinos, that the Rangers were there in case of any attempt to break the condemned man free, but this is pure supposition.

A couple of weeks later, in the 4 March edition of the Star, it was reported that an El Monte meeting held on 23 February culminated in the creation of "a force auxiliary to the Rangers." Twenty-six men signed up as active members, led by Captain John H. Huhes, First Lieutenant James H. Weatherbee, and Second Lieutenant Alexander Puett.

The paper went on to state that " it is in the intention of the company to make immediate application to be received as a military police force and to be supplied with arms, etc." With the organization of the El Monte contingent, it was observed that there were then two mounted units and one foot branch of the Rangers, comprising seventy-two men.

For the Star, the fact that the Rangers had been active in pursuing criminals was evidence that "so long as there are thieves and villains, their organization will be a necessity to the community." The article concluded by noting that a meeting would soon be held among the various branches t choose battalion officers and "for a more perfect organization of this force."

If there was such a gathering, it was not reported on in the Star, though the paper did note the first anniversary of the formation of the Rangers in its issue of 10 August.

As matter-of-fact as the press reporting about the Star was concerning the formation and the activities of the Rangers, the next post moves to a more fanciful and expressive recollection of the organization from one of its founder members, Horace Bell, through his 1881 memoir Reminiscences of a Ranger.

In the 11 March 1854 edition of the Los Angeles Star it was reported that a detachment of the paramilitary organization had captured some horse thieves at the Rancho La Puente, owned by John Rowland and William Workman in the eastern San Gabriel Valley.

The next week a notable occurrence took place, when on Monday the 13th, the first legal execution conducted in Los Angeles was carried off--this nearly four years after the American legal system was implemented in the county.

Ygnacio Herrera was convicted in the District Court of the murder of Nestor Nartiago [probably Artiaga?] on 17 December 1853 and then sentenced to be hung. The Star's article was remarkable terse and began with the strange statement that, on the 13th, Herrera "celebrated the first judicial execution in this County." This might have been a snide comment about the fact that it took so long to secure a capital murder conviction, despite all of the homicides that had taken place. While the paper noted that the convict "was a Mexican and a soldier," it made no reference to the crime or trial in the piece.

The paper did report that "the arrangements of the Sheriff [James R. Barton] were carried out with much solemnity and propriety, and the execution was witnessed by thousands of people." In those days, executions were very public and people could gather on the hills surrounding the jailyard to view the spectacle.

It was also noted that "the prisoner made an address in which he asserted that there was no justice in our courts" and that "there was considerable sympathy for him manifested among the native population," suggesting that there was a racial or ethnic element to his remarks, even though the victim was a fellow Latino.

|

| The 4 March 1854 edition of the Los Angeles Star reported on the first legal execution in the city and the presence of the Los Angeles Rangers paramilitary group. |

Finally, the Star observed that "a detachment of the Rangers, both horse and foot was in attendance," though it was not stated whether the organization's presence was for general observance, security, or for some other reason. It is tempting to believe that, because of the "considerable sympathy" manifested by Herrera's fellow Latinos, that the Rangers were there in case of any attempt to break the condemned man free, but this is pure supposition.

A couple of weeks later, in the 4 March edition of the Star, it was reported that an El Monte meeting held on 23 February culminated in the creation of "a force auxiliary to the Rangers." Twenty-six men signed up as active members, led by Captain John H. Huhes, First Lieutenant James H. Weatherbee, and Second Lieutenant Alexander Puett.

The paper went on to state that " it is in the intention of the company to make immediate application to be received as a military police force and to be supplied with arms, etc." With the organization of the El Monte contingent, it was observed that there were then two mounted units and one foot branch of the Rangers, comprising seventy-two men.

For the Star, the fact that the Rangers had been active in pursuing criminals was evidence that "so long as there are thieves and villains, their organization will be a necessity to the community." The article concluded by noting that a meeting would soon be held among the various branches t choose battalion officers and "for a more perfect organization of this force."

If there was such a gathering, it was not reported on in the Star, though the paper did note the first anniversary of the formation of the Rangers in its issue of 10 August.

As matter-of-fact as the press reporting about the Star was concerning the formation and the activities of the Rangers, the next post moves to a more fanciful and expressive recollection of the organization from one of its founder members, Horace Bell, through his 1881 memoir Reminiscences of a Ranger.

Thursday, December 17, 2015

The Los Angeles Rangers in the Saddle, September 1853

Within a couple of months of its formation, the Los Angeles Rangers paramilitary group was receiving coverage in the Los Angeles Star newspaper for its actions in the field.

The 17 September 1853 edition of the paper noted that the previous Monday, the 12th, "the Rangers received notice that seven horses had been stolen from this vicinity." Five of the organization's members, W.T.B. Sanford, H. Z. Wheeler, William Getman, John Branning and Cyrus Lyon "were detailed for the pursuit," under Sanford's leadership. As noted here previously, Sanford would be a deputy sheriff and Getman both city marshal and sheriff, albeit for only days before his killing in January 1858.

The group rode north from Los Angeles and headed toward the Santa Clara Valley, passing through today's Santa Clarita via the San Fernando Pass and took "the old Santa Barbara road" (where today's State Route 126 heads west towards Ventura) to see if the thieves were in that direction, as reported. They may, in fact, have been headed to the famed Rancho Camulos, just over the county line in Ventura County, but "they were overtaken by a vaquero, and informed that the thieves were discovered."

At that, two of the company ventured ahead and "without difficulty, secured one of them," while "the other succeeded in escaping, on foot, into the mustard." Recovered were "two horses belonging to Don Julian Olivera." With that, the quintet, after 2 1/2 days on the hunt, returned to Los Angeles by Wednesday night and "their prisoner is now in jail in this city. He is a Sonoreño, named Jesus Vega."

Sanford requested the paper offer his thanks to Vicente de la Osa and Juan Bautista Moreno "for their kind hospitality extended to the expedition." It was reported, however, that "other rancheros demanded of the expedition the highest prices for the services they rendered." Noting that the organization was a volunteer one doing its work without seeking payment or reward, the paper chided that "it would seem but a small think for those whose property is exposed, to freely supply the few necessities of this company." Moreover, the Star observed that "every expedition which the Rangers have undertaken, has been successful" and that "the whole community are under obligations to them."

The article concluded by noting that "the recent expedition of Mr. Brevoort [another Ranger officer], for the arrest of the feloow supposed to be [an] accomplice with Vergara" had received due hospitality and support at the ranchos of La Puente, from William Workman, John Rowland and Rowland's son-in-law John Reed, and Chino, from Isaac Williams.

Manuel Vergara was killed near the Colorado River on suspicion of the murder of Los Angeles merchant David Porter in an ambush on the road to the harbor at San Pedro the prior month, but the alleged accomplice was not named and no further news was offered about the man, who was probably released.

As to Jesús Vega, the suspected horse thief, he was tried on grand larceny charges before the county Court of Sessions on 21 November 1853. The value of the horses taken from Manuel Dominguez of the Rancho San Pedro, but the case file showed no disposition of the case. There is also no listing of Vega as among the Los Angeles County prisoners who served time at San Quentin, so he either was convicted and served his time at the county jail, which seems unlikely, or was found not guilty.

There was one other incident around the same time involving the Rangers. On 21 September 1853, a rape was attempted against Antonia Margarita Workman de Temple, daughter of the William Workman who extended hospitality to the Rangers in the Brevoort chase and wife of recent supervisor and Los Angeles city treasurer F.P.F. Temple, on the Rancho La Merced, in today's South El Monte area.

According to the Star's article on the 24th, Isidro Alvitre rode up to the Temple's adobe residence "and enquired for Mrs. T., who endeavored to deceive him by saying she was in the field. He alighted, however, and seized her around the neck, making known his purpose." When Mrs. Temple struggled, "she broke away from him and escaped into the field," where ranch employees met her and escorted her back to the house. The paper continued that "she returned and found the foul fiend watching her; but on the approach of the men, he mounted his horse and rode off to his father's house."

The Star continued that, the following day, "a detachment of the rangers and many of our substantial citizens, went out to examine the case, and, if necesary, to inflict such punishment as would serve as a warning to all such men, disposed to violate the sanctity of domestic life."

A public meeting was then "called to order by Judge [Jonathan R.] Scott and Samuel Arbuckle, Esq. was appointed chairman, and Hon. S.C. Foster, Secretary." Scott was an attorney and judge, Arbuckly was an attorney, and Foster was soon to be the mayor of Los Angeles and involved in one of the most notorious instances of vigilante justice in early 1855, a topic to be covered here soon.

David W. Alexander, a future two-term sheriff and Los Angeles Ranger, John Reed [mentioned above as a rancher at Rancho La Puente], and Andrés Pico, brother of the last governor of Mexican California, a Californio hero in the Mexican-American War, and frequent vigilante justice particpant, were appointed to find a jury of twelve men to hear the case against Alvitre. It was reported that, upon being arrested, he refused "and offered to send his father or brother for him."

This popular tribunal proceeding's jury was composed of Sanford, Brevoort, Andrew Sublette, Geman, and Ozias Morgan, all active Rangers, as well as Scott, Juan María Sepulveda, H.S. Alanson, J. Minturn, John Brinkerhoff, John Aikin, John W. Shore. When the examination was concluded, during which, evidently, Alvitre's defense was that he was drunk, the Jury naturally found Alvitre guilty and sentenced him to a staggering 250 lashes, a head cropping and that he "he leave the county as soon as his physicians pronounce him able to do so." Moreover, if Alvitre was found to be back in the county "that he be hung."

The punishment was summarily inflicted, perhaps by a member of the Rangers, although there was no identification of who carried out the brutal whipping. The paper observed that "many were in favor of hanging the prisoner on the spot, as he was a notoriously bad character." The article continued that Alvitre "is represented as a man of low intellect, whose instincts have ever been the steal and to stab. He is covered with scars, and must have been engaged in many desperate affrays. He is known to all the rancheros as a great cattle thief."

Alvitre did survive the awful punishment inflicted upon him, but was said to have died the following year--likely from the terrible injuries he received. He became the first of several members of the Alvitre family, which was of long standing in the area known as Old Mission or La Misión Vieja at Whittier Narrows, where the Mission San Gabriel was first located from 1771 to about early 1775 before it moved to its current location. More on that family will be posted here, as well.

The 17 September 1853 edition of the paper noted that the previous Monday, the 12th, "the Rangers received notice that seven horses had been stolen from this vicinity." Five of the organization's members, W.T.B. Sanford, H. Z. Wheeler, William Getman, John Branning and Cyrus Lyon "were detailed for the pursuit," under Sanford's leadership. As noted here previously, Sanford would be a deputy sheriff and Getman both city marshal and sheriff, albeit for only days before his killing in January 1858.

The group rode north from Los Angeles and headed toward the Santa Clara Valley, passing through today's Santa Clarita via the San Fernando Pass and took "the old Santa Barbara road" (where today's State Route 126 heads west towards Ventura) to see if the thieves were in that direction, as reported. They may, in fact, have been headed to the famed Rancho Camulos, just over the county line in Ventura County, but "they were overtaken by a vaquero, and informed that the thieves were discovered."

At that, two of the company ventured ahead and "without difficulty, secured one of them," while "the other succeeded in escaping, on foot, into the mustard." Recovered were "two horses belonging to Don Julian Olivera." With that, the quintet, after 2 1/2 days on the hunt, returned to Los Angeles by Wednesday night and "their prisoner is now in jail in this city. He is a Sonoreño, named Jesus Vega."

Sanford requested the paper offer his thanks to Vicente de la Osa and Juan Bautista Moreno "for their kind hospitality extended to the expedition." It was reported, however, that "other rancheros demanded of the expedition the highest prices for the services they rendered." Noting that the organization was a volunteer one doing its work without seeking payment or reward, the paper chided that "it would seem but a small think for those whose property is exposed, to freely supply the few necessities of this company." Moreover, the Star observed that "every expedition which the Rangers have undertaken, has been successful" and that "the whole community are under obligations to them."

The article concluded by noting that "the recent expedition of Mr. Brevoort [another Ranger officer], for the arrest of the feloow supposed to be [an] accomplice with Vergara" had received due hospitality and support at the ranchos of La Puente, from William Workman, John Rowland and Rowland's son-in-law John Reed, and Chino, from Isaac Williams.

Manuel Vergara was killed near the Colorado River on suspicion of the murder of Los Angeles merchant David Porter in an ambush on the road to the harbor at San Pedro the prior month, but the alleged accomplice was not named and no further news was offered about the man, who was probably released.

As to Jesús Vega, the suspected horse thief, he was tried on grand larceny charges before the county Court of Sessions on 21 November 1853. The value of the horses taken from Manuel Dominguez of the Rancho San Pedro, but the case file showed no disposition of the case. There is also no listing of Vega as among the Los Angeles County prisoners who served time at San Quentin, so he either was convicted and served his time at the county jail, which seems unlikely, or was found not guilty.

|

| This 17 September 1853 article from the Los Angeles Star details activities of the Los Angeles Rangers in the pursuit of suspected horse thieves northwest of the town. |

According to the Star's article on the 24th, Isidro Alvitre rode up to the Temple's adobe residence "and enquired for Mrs. T., who endeavored to deceive him by saying she was in the field. He alighted, however, and seized her around the neck, making known his purpose." When Mrs. Temple struggled, "she broke away from him and escaped into the field," where ranch employees met her and escorted her back to the house. The paper continued that "she returned and found the foul fiend watching her; but on the approach of the men, he mounted his horse and rode off to his father's house."

The Star continued that, the following day, "a detachment of the rangers and many of our substantial citizens, went out to examine the case, and, if necesary, to inflict such punishment as would serve as a warning to all such men, disposed to violate the sanctity of domestic life."

A public meeting was then "called to order by Judge [Jonathan R.] Scott and Samuel Arbuckle, Esq. was appointed chairman, and Hon. S.C. Foster, Secretary." Scott was an attorney and judge, Arbuckly was an attorney, and Foster was soon to be the mayor of Los Angeles and involved in one of the most notorious instances of vigilante justice in early 1855, a topic to be covered here soon.

David W. Alexander, a future two-term sheriff and Los Angeles Ranger, John Reed [mentioned above as a rancher at Rancho La Puente], and Andrés Pico, brother of the last governor of Mexican California, a Californio hero in the Mexican-American War, and frequent vigilante justice particpant, were appointed to find a jury of twelve men to hear the case against Alvitre. It was reported that, upon being arrested, he refused "and offered to send his father or brother for him."

This popular tribunal proceeding's jury was composed of Sanford, Brevoort, Andrew Sublette, Geman, and Ozias Morgan, all active Rangers, as well as Scott, Juan María Sepulveda, H.S. Alanson, J. Minturn, John Brinkerhoff, John Aikin, John W. Shore. When the examination was concluded, during which, evidently, Alvitre's defense was that he was drunk, the Jury naturally found Alvitre guilty and sentenced him to a staggering 250 lashes, a head cropping and that he "he leave the county as soon as his physicians pronounce him able to do so." Moreover, if Alvitre was found to be back in the county "that he be hung."

The punishment was summarily inflicted, perhaps by a member of the Rangers, although there was no identification of who carried out the brutal whipping. The paper observed that "many were in favor of hanging the prisoner on the spot, as he was a notoriously bad character." The article continued that Alvitre "is represented as a man of low intellect, whose instincts have ever been the steal and to stab. He is covered with scars, and must have been engaged in many desperate affrays. He is known to all the rancheros as a great cattle thief."

Alvitre did survive the awful punishment inflicted upon him, but was said to have died the following year--likely from the terrible injuries he received. He became the first of several members of the Alvitre family, which was of long standing in the area known as Old Mission or La Misión Vieja at Whittier Narrows, where the Mission San Gabriel was first located from 1771 to about early 1775 before it moved to its current location. More on that family will be posted here, as well.

Friday, December 11, 2015

The Formation of the Los Angeles Rangers, 1853, Part Two

In the late spring and early summer of 1853, a spate of robberies, murders and other crimes taking place in the Los Angeles region spurred a movement to combat the growing scourge.

The 16 July edition of the Los Angeles Star reported on "a large and highly respectable meeting" at the El Dorado Hotel at which "it was resolved to organize a mounted force for the purpose of protecting the public" from rampant crime.

Among the resolutions was the statement that this force be given the power of "arresting all suspicious persons wherever we may find them and ridding the community of the same in such manner as may be advisable."

Another addressed "all persons who have heretofore harbored robbers or assassins ot furnished them means of escape," warning them that such activities would "be punished with the greatest severity."

Then, there was a "three days warning to the whole vagrant class," including the taking of names and physical descriptions and that "their failure to leave the county in the specified time" would lead to their removal "at all hazards."

Finally, these resolutions concluded with the statement "that we continue the system here adopted until the peace and seciroty of the community are perfectly established."

Along a similar vein, what were the conditions applicable to punishing persons deemed to be assisting criminals and what would the "greatest severity" mean with respect to the punishment?

Vagrancy could, presimably, imply a wide variety of attributes imputed to someone deemed to be a "vagrant." Was such a person unemployed or seasonally employed? What other factors would be taken into account to determine vagrancy? And, again, their removal from the county "at all hazards," implied that any sort of force would be available for use.

Finally, how would the community, or at least those taking it upon themselves to act for the community, know that there was a "perfectly established" sense of "peace and security," at which time the measures adopted at the meeting would be relaxed?

Notably, this addressing of vagrancy predated by two years the passage of a state law, titled “An Act to Punish Vagrants, Vagabonds, and Dangerous and Suspicious Persons,” that addressed all manner of miscreants, from prostitutes and drunks to "healthy beggars" and ordered that those "with no visible means of living" get a job within ten days and that "lewd and dissolute persons" as well as prostitutes and drunks serve up to 90 days at hard labor for their indiscretions.

Another result of the meeting was that "a company was then formed" to carry out the mandate ratified at the gathering. Leadership of the organization was given to Benjamin D. Wilson, late mayor of Los Angeles and a future state senator, who had no subordinates. Even though the meeting was held just the previous day, the Star reported that "some have already started out" on the work of protecting the county.

Meantime, it was said that sixteen men at El Monte organized at their own meeting to support Wilson's company and that Charles H. Wurden of that community was elected captain of that auxiliary.

This followed a slightly earlier effort from early June, in which a meeting held on the 7th led to the creation of an organization called the "Los Angeles Guards," featurng thirty members, led by David W. Alexander, a future sheriff, attorney and judge Myron Norton, future Southern Californian publisher John O. Wheeler, common council member and future state treasurer Antonio Franco Coronel, and Samuel K. Labatt. The Star observed that "such an organization would be a great means of securing good order in our city." A little more than two weeks later, a formal election of officers was held, with Wheeler named Captain, Norton first lieutenant, Alexander second lieutenant, and merchant Solomon Lazard elected as third lieutenant. It was also reported that the member roll had doubled to sixty.

It is unclear how much actual crime-fighting was undertaken by the Guards and by Wilson's company, but the Los Angeles Rangers, which also organized during the summer, definitely had more activity. The 6 August 1853 issue of the Star reported that there were 100 enrolled members and a quarter of them were deemed to be active. Moreover, the paper continued, "their horses [are] to be furnished gratuitously [sic] by the rancheros, as a loan to the company, with other costs to be assumed by the county "and private subscription." For example, the Board of Supervisors earmarked $1000 for arms and expected to be reimbursed for such by the state.

A little over a month later, the first major reported activity of the Rangers appeared in the Star. More on that and other developments in a post coming soon.

The 16 July edition of the Los Angeles Star reported on "a large and highly respectable meeting" at the El Dorado Hotel at which "it was resolved to organize a mounted force for the purpose of protecting the public" from rampant crime.

Among the resolutions was the statement that this force be given the power of "arresting all suspicious persons wherever we may find them and ridding the community of the same in such manner as may be advisable."

Another addressed "all persons who have heretofore harbored robbers or assassins ot furnished them means of escape," warning them that such activities would "be punished with the greatest severity."

Then, there was a "three days warning to the whole vagrant class," including the taking of names and physical descriptions and that "their failure to leave the county in the specified time" would lead to their removal "at all hazards."

Finally, these resolutions concluded with the statement "that we continue the system here adopted until the peace and seciroty of the community are perfectly established."

Along a similar vein, what were the conditions applicable to punishing persons deemed to be assisting criminals and what would the "greatest severity" mean with respect to the punishment?

Vagrancy could, presimably, imply a wide variety of attributes imputed to someone deemed to be a "vagrant." Was such a person unemployed or seasonally employed? What other factors would be taken into account to determine vagrancy? And, again, their removal from the county "at all hazards," implied that any sort of force would be available for use.

Finally, how would the community, or at least those taking it upon themselves to act for the community, know that there was a "perfectly established" sense of "peace and security," at which time the measures adopted at the meeting would be relaxed?

Notably, this addressing of vagrancy predated by two years the passage of a state law, titled “An Act to Punish Vagrants, Vagabonds, and Dangerous and Suspicious Persons,” that addressed all manner of miscreants, from prostitutes and drunks to "healthy beggars" and ordered that those "with no visible means of living" get a job within ten days and that "lewd and dissolute persons" as well as prostitutes and drunks serve up to 90 days at hard labor for their indiscretions.

Another result of the meeting was that "a company was then formed" to carry out the mandate ratified at the gathering. Leadership of the organization was given to Benjamin D. Wilson, late mayor of Los Angeles and a future state senator, who had no subordinates. Even though the meeting was held just the previous day, the Star reported that "some have already started out" on the work of protecting the county.

Meantime, it was said that sixteen men at El Monte organized at their own meeting to support Wilson's company and that Charles H. Wurden of that community was elected captain of that auxiliary.

|

| The 8 June 1853 issue of the Star reported on the formation of the Los Angeles Guards, another organization intended to fight crime in the region. |

It is unclear how much actual crime-fighting was undertaken by the Guards and by Wilson's company, but the Los Angeles Rangers, which also organized during the summer, definitely had more activity. The 6 August 1853 issue of the Star reported that there were 100 enrolled members and a quarter of them were deemed to be active. Moreover, the paper continued, "their horses [are] to be furnished gratuitously [sic] by the rancheros, as a loan to the company, with other costs to be assumed by the county "and private subscription." For example, the Board of Supervisors earmarked $1000 for arms and expected to be reimbursed for such by the state.

A little over a month later, the first major reported activity of the Rangers appeared in the Star. More on that and other developments in a post coming soon.

Friday, December 4, 2015

The Formation of the Los Angeles Rangers Miltary Company, 1853

In the first few years of the American era, crime was rampant in the Los Angeles region and law enforcement and the courts were poorly funded, short staffed and saddled by standards of evidence that made arrests and securing convictions tough.

As a response, citizens frequently formed militias and paramilitary organizations that were formed ostensibly to make up for the shortfall and fight crime. Many of these wound up being more like social clubs (drinking parties) than crime-fighting organizations, but occasionally there were some that served as the latter.

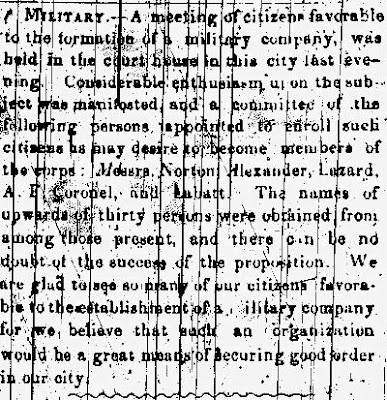

The best known was the Los Angeles Rangers. By mid-1853, frustration with unmitigated crime led to a community meeting. The 8 July issue of the Los Angeles Star featured an article that covered the gathering held at the court house.

It was noted that "considerable enthusiasm . . . was manifested" about forming a military company and a committee was formed to recruit members. This group featured Myron Norton, a judge and attorney, Henry N. Alexander, who had various law enforcement roles, merchant Solomon Lazard, S.K. Labatt, and Antonio Franco Coronel, the sole Latino in the effort and who was a councilman, mayor and later California state treasurer.

From those attending the gathering, some thirty expressed an interest in joining, from which the paper observed, "we are glad to see so many of our citizens favorable to the establishment of a military company" because this "would be a great means of securing good order in our city."

In any case, the Rangers were in operation and future posts will cover more about this group and its efforts during the era.

As a response, citizens frequently formed militias and paramilitary organizations that were formed ostensibly to make up for the shortfall and fight crime. Many of these wound up being more like social clubs (drinking parties) than crime-fighting organizations, but occasionally there were some that served as the latter.

The best known was the Los Angeles Rangers. By mid-1853, frustration with unmitigated crime led to a community meeting. The 8 July issue of the Los Angeles Star featured an article that covered the gathering held at the court house.

It was noted that "considerable enthusiasm . . . was manifested" about forming a military company and a committee was formed to recruit members. This group featured Myron Norton, a judge and attorney, Henry N. Alexander, who had various law enforcement roles, merchant Solomon Lazard, S.K. Labatt, and Antonio Franco Coronel, the sole Latino in the effort and who was a councilman, mayor and later California state treasurer.

From those attending the gathering, some thirty expressed an interest in joining, from which the paper observed, "we are glad to see so many of our citizens favorable to the establishment of a military company" because this "would be a great means of securing good order in our city."

|

| The 8 July 1853 issue of the Los Angeles Star covered a citizens' meeting held at the county court house for the formation of a military company, which became the Los Angeles Rangers. |

Within a short time, the formal organization of the Rangers was achieved. On 6 August, the same day that it was reported that the notorious bandido Joaquin Murieta had been captured in northern California (or so it was alleged), the Star published an article detailing the creation of the paramilitary group.

The piece started off by noting that "the people of this county have long felt the necessity of having among them an efficient milirary force, which could be brought out promptly to aid of the laws and for the protection of life and property."

However, the article continued, "we are not only exposed to regular predatory visits from indians from the neighboring mountains, who come here to feed on cattle and carry off horses" but "we have seen organized band of robbers, well mounted and well armed, traversing the country unmolested" and stealing horses to the extent that "it is universally admitted that the roads are unsafe to travel."

|

| This 6 August 1853 article from the Star discussed the necessity for the formation of the Los Angeles Rangers paramilitary company due to rampant crime and violence in the Los Angeles region. |

The piece observed that there had been "numerous robberies" as well as "two fearful murders almost in the streets of Los Angeles—which have taken place within the last two months."

Unlike in northern California, evidently, the problem in the Los Angeles County region was that "it is very difficult for us to concentrate, in due time, a sufficient number of men suitably armed and mounted, to pursue offenders successfully."

There was, however, a thinly-veiled criticism of at least part of the ethnic majority population of the area, Spanish-speaking Californios and Mexicans, as the paper alleged that

The well disposed citizens, also, have peculiar obstavles to contend with here, in any effort of the kind such as, we believe, exist in no other part of the United States: we speak of the habitual concealment of offenders and the repugnance to give information to the authorities, of which a large class of our population is justly accused.While the Star averred that these sympathetic enablers were "justly accused," it offered no statistics, examples or any kind of specifics to back up the generalization, nor did it seem open to the fact that criminals might have been using intimidation or other forms of influence or pressure on locals to look the other way and disavow cooperation with the police. This is not to suggest that there was no truth to the paper's assertions, but there was also nothing specific cited to buttress the argument either.

In any case, the Rangers were in operation and future posts will cover more about this group and its efforts during the era.

Monday, November 30, 2015

This Picture's Thousand Words: Los Angeles from Fort Hill, ca. 1870

Number one is the gent standng on New High Street in the center foreground. Dressed in a dark suit, white shirt, and light-colored hat, our subject is also carrying a shotgun in his hands. This would seem to indicate that he was one of the handful of constables who patrolled the town.

The next item of interest takes us to the top center of the photo, where the conspicuous clock tower shows that the time was a little before 12:45 p.m. on whatever day Godfrey took the photo, or whatever day the clock stopped working prior to that! The building which the tower surmounted was built as the city's market house in 1859 by merchant Jonathan Temple.

As earlier posts here have noted, the structure was leased to the city and county for public offices and the courthouse. It served in this capacity until the late 1880s, when separate structures were built for the city hall and courthouse. The "Old Courthouse" as it was sometimes known was torn down shortly afterward and replaced by the Blanchard Building. In the last half of the 1920s, this area, known as the Temple Block, because of several buildings constructed by Jonathan Temple and his half-brother between 1857 and 1871, was redeveloped for the new city hall, completed in 1928.

Finally, there is the site behind the armed gentleman and the building next to him. Fronting Temple Street is a white adobe wall and a two-part wooden gate with a crossbeam atop it. This is the Tomlinson and Griffith lumberyard, located at the corner of New High and Temple streets, a bit of the latter is at the far right, where the ox-team is in view.

John J. Tomlinson was an early proprietor of a stagecoach line form the rudimentary port at San Pedro and a fierce rival of Phineas Banning, who, along with Banning, became a lumberman in 1860. Shortly afterward, his brother-in-law, John M. Griffith, came to Los Angeles and the two men became partners in both the stagecoaching and lumbering businesses until Tomlinson died in 1868.

Griffith then took on a new part, Santa Cruz lumber magnate Sedgwick J. Lynch, who was looking to expand his empire as Los Angeles began its first sustained growth period just around the time that Tomlinson died. Griffith, Lynch and Company prospered as the city needed more lumber to accommodate the construction demands of the growing town.

Unfortunately, there was another unforeseen demand placed upon the lumberyard--the use of its gate and crossbeam as a convenient gallows for lynch (somewhat ironic given the name of one its partners) mobs to conduct their extralegal business.

According to prominent merchant Harris Newmark, a late 1863 lynching of Charles Wilkins (to be covered here in more depth later) took place

on Tomlinson & Griffith's corral gateway where nearly a dozen culprits had already forfeited their lives.Given that Tomlinson, according to Newmark, had only embarked in the lumbering business three years prior, it is unclear how "nearly a dozen culprits" had been hung there, unless there had been a prior owner of the property.

Seven years later, at the end of 1870, Michel Lachenais, who had committed several homicides and been acquitted twice in Los Angeles courts, murdered his neighbor Jacob Bell over a property dispute (again, this case will be profiled here at a future time), and, as noted by Newmark

three hundred or more men . . . took Lachenais out [of the jail], dragged him along to the corral of Tomlinson & Griffith . . . and there summarily hanged him.The Lachenais lynching has the distinction (if it can be so called) of being the only one that was photographed--also by Godfrey. This photo has been published in many books and articles over the years and is easily one of the best-known images of a benighted "City of Angels."

Finally, there was the one event that constituted the biggest blot on Los Angeles in its early history and perhaps of all of its existence: the Chinese Massacre of October 24, 1871. After an internal dispute among the small, but growing, Chinese community led to gunfire and the death of an American who interjected himself into the battle, a mob of perhaps 500 or so men stormed the Calle de los Negros east of the Plaza,where Los Angeles Street heads towards Alameda Street and lynched nineteen Chinese males, including a teenaged boy. Once more, this event will be given a fuller treatment here, but among the locations where the horrors were perpetrated was, as Newmark again noted,

up Temple to New High street, where the familiar framework of the corral gates suggested its use as a gallows.It appears that there was just one victim hung at the corral and there would have been more, except that Sheriff James Burns and citizens Robert Widney (accused by Horace Bell, another, more fanciful, chronicler of the time, of leading the Lachenais lynching--though this is not at all proven), Cameron Thom, the district attorney, and H.C. Austin assisted in saving at least one other man.

Fortunately, there were no more lynchings in the city after this and it was said that Griffith was so angered by what had happened that he ordered the gate and beam removed to prevent its further use by lawless mobs.

It is tempting to think that Godfrey set up this photo as some kind of reference to Los Angeles and its lawlessness. Having an armed constable (if that's who the gent was), the Tomlinson & Griffith corral, and the county courthouse in view seems coincidental. We'll never know, unless Godfrey left a diary that hasn't yet seen the light of day!

Wednesday, November 25, 2015

The Big House II: San Quentin State Prison and Los Angeles County Inmates

In April 1853, the second and third Los Angeles County prisoners to become inmates at San Quentin State Prison (and the 195th and 196th overall) were shipped up and admitted to the new facility.

Henry King and Juan, an Indian, were both tried in the Court of Sessions, presided over by the county judge and two associates selected from among the justices of the peace in the townships outside Los Angeles.

King was under indictment for grand larceny against a person or persons unidentified in the surviving court docket and was convicted on 6 April. He was sentenced to two years at San Quentin. Juan, was convicted of the rape of Juana Ybarra, on the following day, the 7th. Although the docket does not indicate sentence, the San Quentin register recorded it as eight years.

A 38-year old native of Pennsylvania, King's occupation was millwright, which traditionally meant someone who was involved in the construction of water or wind mills, but who could also have done work on textile mills, agricultural machinery and other types of work involving the use of machinery in production. The 5'5" convict was described as having scars on his chin and neck near his throat, as well as both legs and two warts on his right hand.

Juan was a 21-year old, 5' 5 1/4" in height, and described as having a "broad nose, thick lips, scar right side of nose, large scar on head." His occupation was "vaquaro" or vaquero.

Notably, while King was listed as having been discharged, though with no specific date, Juan had no such comment in his listing, leading to the question of what happened to him.

In a review of over 1,200 court cases between 1850 and 1875, it was found that larcenies (including grand, which involved over $50 in property value, and petit [petty] for less than that amount) constituted about one-third of all crimes.

The San Quentin register of Los Angeles County-based convicts showed that almost half of the 168 men sent there prior to 1865 were sent there because of grand larcenies. For the total of 354 to the end of 1875, the number was about 45%.

Rape, the crime for which Juan was found guilty, was, however, far less frequent.

Only 11 of the 354 Los Angeles County inmates at San Quentin were there for rape convictions, forming but 3% of the total. Of course, it has to be stated that rape was almost certainly a crime that was scarcely reported, much less prosecuted, largely because women were highly unlikely to alert officials to the crime.

In the court records, there were fifteen men charged with rape or assault to commit rape prior to 1865. For the decade from 1865-1875, there were thirteen cases of rape or assault to commit rape, with one example, in 1873, comprising a charge of a "crime against nature" regarding a male defendant and male victim. In all, about 2% of all criminal cases in existing records involved rape charges.

As Los Angeles grew, but, more importantly, as its courts began to secure more convictions, the number of men sent to San Quentin grew. From 1852-55, only 14 men were sent up to the "big house," a number equaled in 1856 alone. Future posts will deal with more Los Angeles County convicts sent to San Quentin, so check back here for more on that fascinating subject.

Henry King and Juan, an Indian, were both tried in the Court of Sessions, presided over by the county judge and two associates selected from among the justices of the peace in the townships outside Los Angeles.

King was under indictment for grand larceny against a person or persons unidentified in the surviving court docket and was convicted on 6 April. He was sentenced to two years at San Quentin. Juan, was convicted of the rape of Juana Ybarra, on the following day, the 7th. Although the docket does not indicate sentence, the San Quentin register recorded it as eight years.

A 38-year old native of Pennsylvania, King's occupation was millwright, which traditionally meant someone who was involved in the construction of water or wind mills, but who could also have done work on textile mills, agricultural machinery and other types of work involving the use of machinery in production. The 5'5" convict was described as having scars on his chin and neck near his throat, as well as both legs and two warts on his right hand.

Juan was a 21-year old, 5' 5 1/4" in height, and described as having a "broad nose, thick lips, scar right side of nose, large scar on head." His occupation was "vaquaro" or vaquero.

Notably, while King was listed as having been discharged, though with no specific date, Juan had no such comment in his listing, leading to the question of what happened to him.

In a review of over 1,200 court cases between 1850 and 1875, it was found that larcenies (including grand, which involved over $50 in property value, and petit [petty] for less than that amount) constituted about one-third of all crimes.

The San Quentin register of Los Angeles County-based convicts showed that almost half of the 168 men sent there prior to 1865 were sent there because of grand larcenies. For the total of 354 to the end of 1875, the number was about 45%.

Rape, the crime for which Juan was found guilty, was, however, far less frequent.

Only 11 of the 354 Los Angeles County inmates at San Quentin were there for rape convictions, forming but 3% of the total. Of course, it has to be stated that rape was almost certainly a crime that was scarcely reported, much less prosecuted, largely because women were highly unlikely to alert officials to the crime.

In the court records, there were fifteen men charged with rape or assault to commit rape prior to 1865. For the decade from 1865-1875, there were thirteen cases of rape or assault to commit rape, with one example, in 1873, comprising a charge of a "crime against nature" regarding a male defendant and male victim. In all, about 2% of all criminal cases in existing records involved rape charges.

As Los Angeles grew, but, more importantly, as its courts began to secure more convictions, the number of men sent to San Quentin grew. From 1852-55, only 14 men were sent up to the "big house," a number equaled in 1856 alone. Future posts will deal with more Los Angeles County convicts sent to San Quentin, so check back here for more on that fascinating subject.

Sunday, November 22, 2015

Early Los Angeles Jails: The Good, the Bad and the Ugly, 1858-1861

It is interesting to see that, as the 1850s closed and the next decade dawned, the condition of the county and city jail facility varied somewhat considerably over a several-year period.

El Clamor Público, for example, reprinted the report of the Grand Jury in its 17 July 1858 edition, with foreman F.P.F. Temple, stating,

Peterson wrote that "an inspection of the jail affords satisfactory evidences of the efficiency of the gentleman in charge—Mr. Mitchell; and that due regard is paid to the cleanliness and good order of the prison and the health and security of its inmates."

In late November, another Grand Jury report found matters were generally well under the management of new jailer, Francis Carpenter, observing, as reprinted in the 26 November edition of the Star that they "find the prison and all the cells in a clean and healthy condition." Carpenter, the report went on, "deserves great credit for the good order and management manifested by him, in the whole and every portion of said jail."

Interestingly, this report featured an element not generally found in others, the apparent interviewing of incarcerated prisoners as part of the review. The report stated that "nor do we find any complaint whatever from those confirned therein. of the management or the treatment of the jailer." It concluded by noting that "the prison yard is in good and cleanly order; and with two exceptions only, we find everything satisfactory. amd requiring no particular alteration or improvement.

The main exception was that

More specifically, the jury exhibited its concerns regarding, "the want of conveniences, too, for the imperative calls of nature" and requested the Board of Supervisors to do something "whereby this serious deficiency may be obviated."

Yet, in the July report, the jury merely stated that "they have . . . visited the county jail, and found the same cleanly, and in good condition." Two months later, another jury was equally sanguine, reporting that it was "clean, in good order, and well kept." By these very terse reports, it would seem that at least some of the concerns of the November and March reports were dealt with.

Except that the November 1860 Grand Jury not only deviated from these, but great expanded upon the statements of its predecessory from exactly a year prior. Foreman J.F. Stephens reported, as reprinted in the 24 November issue, that

Also of note was the fact that "prisoners were frequently put in and taken out of jail by the township officers [from outlying areas of the county], without the knowledge of the person in charge."

Given these issues, the jury recommended that "the general condition of the jail, no less than the safekeeping of the prisoners, imperatively demands a thorough change in the management and direction to all things relating to the county prison."

The 9 March 1861 edition of the Star reprinted the Grand Jury report, as subscribed by foreman George W. Gift, and the only problem cited with the jail had to do with "some repairs [to] be had upon the wall surrounding it," otherwise the jury felt that "in all other respects, our visit to the Jail was satisfactory."

Yet, Gift noted something with respect to the fact that "a very great evil exists in the present mode of administering justice to the Indian petty criminals who are convicted before the Justices of the Peace throughout the county." Specifically citing the statute dealing with "the government and protection of Indians in this state," Gift observed that punishments for the petty theft required uo to twenty-five lashes. Not only was "this mode of punishment . . . very seldom resorted to," but that "our prisons are burdened with this class of criminals, at a very great expense to the county."

Beyond that, it was claimed in the report, "the Indians themselves, it may be said, hardly consider imprisonment, coupled with good board, a punishment; but, on the contrary, deem it a reward." Consequently, this section concluded,

Another notable situation involved a grand larceny suspect already serving a sentence for petty larceny, which involved his being sent out as a laborer on a nearby ranch or farm, from which he escaped. It was another six months before his recapture, by which time the sole witness in the grand larceny matter had left the area. Then, although his petty larceny sentence expired, the man "still is in jail, without any proceedings, having taken place in his case.

Other examples were cited of cases dealing with the charge of assaults with deadly weapons, yet all lacked "sufficient evidence to warrant the finding of [true] bills" while "the accused have been for periods of greater or less duration in prison." With these matters involving "a serious wrong," the jury noted that, in examples of innocence, "great injustice is done to the individual," while, for the guilty, "the accused only becomes more hardened and depraved through his incarceration, without the ends of the ends of justice being attained." Moreover, these imprisonments meant that "the county has been unnecesarily unburdened with expense."

Then, there was the condition of the jail. The jurors noted that

Moreover, the report contined, "the prisoners in the jail complain of the quality and quantity of the food furnished them, and the infrequency of their meals." Morning rations included just "a cup of unpalatable coffee" and "a small piece of bread." The noon meal consisted of "a pint of vegetable soup and also meat, but that the latter from its quality and want of cleanliness and care in cooking, is objectionable." Remarkably, a full 19 hours passed before the morning meal was provided. Sheriff Tomás Sanchez told the jury that, on this latter point, "he was guided by the advice of the visiting physician."

Less than two weeks later, in the 24 July 1861 edition of the Los Angeles News, another problem was reported "in regard to the criminal looseness and carelessness with which our county jail is conducted." Siriaco Arza, awaiting trial for murder, "was discovered by an officer in the street, and at liberty." Another inmate, under a fice-month sentence, was discovered missing. A police officer "heard of his whereabouts, and infomed the jailor, inquiring what reward would be paid for his capture." The reply was that, because the man had served two months for the petty offense, "that was sufficient," meaning he did not need to be retaken and returned to jail.

Outraged, the News demanded that "this matter should be thoroughly investigated," stating that "it is not thus that our county jail, where some of the worst criminals are sometimes confined, should be managed." Sheriff Sanchez, who appointed the jailer, was responsible for the problem and "is hihgly censurable for appointing a man so unfit and irresponsible." The paper insisted that "the investigation into the affairs of the prison should be severe, and those persons who are guilty ought to be severely punished."

By 1861, the county was in some desperate financial straits, as the end of the Gold Rush, a glut in the cattle market which formed the region's economic backbone, the depression of 1857 and other factors were at play. Taxpayers were loath, even in flush times, to pay for even the most basic of amenities. Finally, it appears that jail conditions were also heavily dependent on the good offices of the county sheriff and his appointed jailer.

Generally, matters appeared to have improved after the early 1860s, but there seems little question that, for extended periods, the jail was poorly managed and maintained for much of the 1850s and first part of the following decade.

|

| The Grand Jury report, as reprinted in El Clamor Público, 17 July 1858. |

El Gran Jurado ha visitado y examinado la Carcel del Condado, y encuentra que bajo al manejo del actual carcelero se suplen todas las necesidades de los prisioneros, y se pone la atencion debida al aseo y ventilacion de la carcel.

The Grand Jury has visited and examined the County Jail, and found that under the management of the jailer, all the necessities of the prisoners have been provided and he has given the necessary attention for the cleanliness and ventilation of the jail.In late winter 1859, another Grand Jury report was issued and reproduced both by El Clamor Público and the Los Angeles Star with William H. Peterson, a former deputy sheriff, serving as foreman. While Peterson wrote a scathing indictment of the "Indian alcade system," referred to in a previous post in this blog concerning the use of Indians arrested for drunkenness for servile labor, noting that it was "daily productive of evil and deserving of unqualified condemnation," he was highly complimentary when it came to the jail.

Peterson wrote that "an inspection of the jail affords satisfactory evidences of the efficiency of the gentleman in charge—Mr. Mitchell; and that due regard is paid to the cleanliness and good order of the prison and the health and security of its inmates."

In late November, another Grand Jury report found matters were generally well under the management of new jailer, Francis Carpenter, observing, as reprinted in the 26 November edition of the Star that they "find the prison and all the cells in a clean and healthy condition." Carpenter, the report went on, "deserves great credit for the good order and management manifested by him, in the whole and every portion of said jail."

|

| The Los Angeles Star reprinting of the report of the Grand Jury in its 26 November 1859 edition. |

The main exception was that

There is on the main upper room of the prison, a prisoner affected with a loathsome disease, from whence proceeds a stench which is almost intolerable. The other persons confined in that part of the prison, are now obliged to be in contact with this intolerable nuisance, and, we believe, the dangerous effluvia proceeding from the disease. These persons are human beings, and we think should not be thus exposed to such nuisances; we therefore recomment that the diseased man should be at once removed.The Star of 10 March 1860 featured another Grand Jury report showed that there were some further concerns amidst general satifaction. Foreman O.P. Passons [listed as Parsons] wrote that the condition of the facility "is deserving of approval", but went on to "suggest that additional whitewashing and ventilation woulkd contribute greatly to the promotion of the health of the inmates, and relieve the jailor from much labor which the want of these renders necessary."

More specifically, the jury exhibited its concerns regarding, "the want of conveniences, too, for the imperative calls of nature" and requested the Board of Supervisors to do something "whereby this serious deficiency may be obviated."

Yet, in the July report, the jury merely stated that "they have . . . visited the county jail, and found the same cleanly, and in good condition." Two months later, another jury was equally sanguine, reporting that it was "clean, in good order, and well kept." By these very terse reports, it would seem that at least some of the concerns of the November and March reports were dealt with.

Except that the November 1860 Grand Jury not only deviated from these, but great expanded upon the statements of its predecessory from exactly a year prior. Foreman J.F. Stephens reported, as reprinted in the 24 November issue, that

After proper examination it was with regret that we had much to condemn. The several apartments were in very bad condition; emitting from heaps of filth that had been sufferent to accumulate, a most unwholesome and offensive stench. The sick prisoners, of whom there are two, complain of a lack of proper medical attendance and suitable food. We deem it highly important that the entire premises should be immediately cleansed and precautions taken to insure greater cleanliness for the future.Taking the jailer to task because of "absence, negligence and incapacity," the jurors went on to note that "several persons, committed for petty offences, were detained some weeks after their term of sentence had expired." Yet, there was another prisoner who was sentenced to six months and a $30 fine, but "was discharged by the jailor, without authority, after three days of imprisonment. Then, there was an Indian who was held on "some undefined charge, and suffered to remain over two months, without examination or commitment."

|

| A very critical Grand Jury report, published in the Star, 24 November 1860. |

Given these issues, the jury recommended that "the general condition of the jail, no less than the safekeeping of the prisoners, imperatively demands a thorough change in the management and direction to all things relating to the county prison."

The 9 March 1861 edition of the Star reprinted the Grand Jury report, as subscribed by foreman George W. Gift, and the only problem cited with the jail had to do with "some repairs [to] be had upon the wall surrounding it," otherwise the jury felt that "in all other respects, our visit to the Jail was satisfactory."

Yet, Gift noted something with respect to the fact that "a very great evil exists in the present mode of administering justice to the Indian petty criminals who are convicted before the Justices of the Peace throughout the county." Specifically citing the statute dealing with "the government and protection of Indians in this state," Gift observed that punishments for the petty theft required uo to twenty-five lashes. Not only was "this mode of punishment . . . very seldom resorted to," but that "our prisons are burdened with this class of criminals, at a very great expense to the county."

Beyond that, it was claimed in the report, "the Indians themselves, it may be said, hardly consider imprisonment, coupled with good board, a punishment; but, on the contrary, deem it a reward." Consequently, this section concluded,

We say, whip the Indians at once, and stop that expense of their keeping in the County Jail.Matters worsened in the next report, as detailed in the 13 July issue of the Star. Foreman J.J. Warner's statement echoed that of the November 1860 report in that there were several examples of prisoners confined because of a lack of due process. In one instance, a prisoner was in the jail for over a month without an examination before a judge and the jury determined that the matter lacked "any inquiry or proof of malice on the part of the accused." In addition to the wrong of having the individual confined for weeks without reason, there as also the fact that "the county [was] made chargeable with his support and the costs arising from the commitment."

Another notable situation involved a grand larceny suspect already serving a sentence for petty larceny, which involved his being sent out as a laborer on a nearby ranch or farm, from which he escaped. It was another six months before his recapture, by which time the sole witness in the grand larceny matter had left the area. Then, although his petty larceny sentence expired, the man "still is in jail, without any proceedings, having taken place in his case.

Other examples were cited of cases dealing with the charge of assaults with deadly weapons, yet all lacked "sufficient evidence to warrant the finding of [true] bills" while "the accused have been for periods of greater or less duration in prison." With these matters involving "a serious wrong," the jury noted that, in examples of innocence, "great injustice is done to the individual," while, for the guilty, "the accused only becomes more hardened and depraved through his incarceration, without the ends of the ends of justice being attained." Moreover, these imprisonments meant that "the county has been unnecesarily unburdened with expense."

Then, there was the condition of the jail. The jurors noted that

we found the rooms of the prison filled with a foul and disagreeable atmosphere. The walls of the rooms are yellow and discolored by noxious vapors. From an unpardonable neglect, the conducting pipes from a water closet used by a large proportion of the inmates of the prison, had been suffered to remain in a leaky condition until the floor of the room became saturated.Despite some repairs involving the covering of the water closet floor with metal, "the atmosphere of the prison . . . was highly impregnated with a most offensive and unhealthy effluvia." For reasons of comfort, health, economizing "and the reputation of the county," it was recommended that "a much higher degree of cleanliness" be employed throughout the facility, which was only cleaned every eight days. Considering the size of thh spaces, the number of prisoners and the infrequency of cleaning, it was evident to the jury that "the rooms must become prejudician to the health of those confined therein."

|

| A particularly visceral report from the Grand Jury, from the Star's issue of 13 July 1861. |

Less than two weeks later, in the 24 July 1861 edition of the Los Angeles News, another problem was reported "in regard to the criminal looseness and carelessness with which our county jail is conducted." Siriaco Arza, awaiting trial for murder, "was discovered by an officer in the street, and at liberty." Another inmate, under a fice-month sentence, was discovered missing. A police officer "heard of his whereabouts, and infomed the jailor, inquiring what reward would be paid for his capture." The reply was that, because the man had served two months for the petty offense, "that was sufficient," meaning he did not need to be retaken and returned to jail.

Outraged, the News demanded that "this matter should be thoroughly investigated," stating that "it is not thus that our county jail, where some of the worst criminals are sometimes confined, should be managed." Sheriff Sanchez, who appointed the jailer, was responsible for the problem and "is hihgly censurable for appointing a man so unfit and irresponsible." The paper insisted that "the investigation into the affairs of the prison should be severe, and those persons who are guilty ought to be severely punished."

By 1861, the county was in some desperate financial straits, as the end of the Gold Rush, a glut in the cattle market which formed the region's economic backbone, the depression of 1857 and other factors were at play. Taxpayers were loath, even in flush times, to pay for even the most basic of amenities. Finally, it appears that jail conditions were also heavily dependent on the good offices of the county sheriff and his appointed jailer.

Generally, matters appeared to have improved after the early 1860s, but there seems little question that, for extended periods, the jail was poorly managed and maintained for much of the 1850s and first part of the following decade.

Tuesday, November 17, 2015

Early Los Angeles Jails: New and Unimproved, 1854-1858

The Los Angeles city and county jail built in 1853-54 in the courtyard of the Rocha Adobe, which also served as the county courthouse, might have been new, but it wasn't long before its defects became public.

The Southern Californian newspaper, a new journal, reprinted a report of the Grand Jury in its 16 November 1854, in which it stated that the jail was filthy and was in desperate need of cleaning.

The 1 March 1855 edition of the Southern Californian reported, in its inimitable style, that, in the midst of heavy rains, prisoners at the city portion of the jail on the first floor were not out doing public works in the chain gang and remained confined, so,

A little over a year later, another unsavory aspect of the jail came to light when the Star, on 17 May 1856, reported that county prisoner José Dominguez, died in the facility, becoming the second such case recently. Dominguez, who was found guilty of Grand Larceny in the District Court in early January, was sentenced to five months' imprisonment, so it appears he was only a couple of weeks away from release when he died of "bilious fever." The paper observed that

The Star added that there was an unnamed German prisoner who "was mercifully removed from the jail to a proper place, and thus only [italics original] recovered; let us have the same rule as to all classes of prisoners."

Another year-and-a-half went by before news of the jail's condition were discussed, but this time it was to report a rare example of improvement. The Star of 14 November 1857 noted that "a great improvement has also been made in the County Buildings. A brick pavement has been laid down in front, a substantial fence put up, and the court-house and jail, with the public offices, thoroughly repaired and cleaned."

Two months later, in its 30 January 1858 edition, the paper's editor, Henry Hamilton, visited the jail and was given a tour by jailer Joseph H. Smith. Hamilton noted the recent changes, noting that "the yard is neat and clean" and added that shrubs were planted "which will prove ornamental and tend to relieve the harsh outline incidental to the narrow enclosure" of the adobe.

Hamilton went on to give the most detailed description we have of the jail, observing that the first floor section for the city had two rooms for the separation of men and women, with "the occupants of the latter, we need scarcely say, being of the 'bow and arrow' tribe." There were, however, no beds and inmates "may select a soft spot in the earthen floor to sleep off a 'drunk," although "the jailer does his duty in keeping the apartments clean."